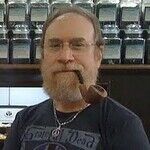

At 56, I set myself an aggressive goal: win a master's tennis tournament by 60. The only problem was that I'd been playing tennis for two months. But I've always been athletic. Lifelong soccer player, squash tournament winner, the kind of person who rode a bicycle through Vietnam in the 1990s because that seemed like a reasonable thing to do.

The plan was on track until this year, when my body delivered an invoice I couldn't ignore. Turns out that playing hard, relying on athletic tenacity to outwill opponents, works brilliantly — until your fifth decade, when it starts working against you in ways that compound faster than you notice.

I'm writing this two weeks after my seventh athletic surgery. Three on my left knee starting in 1986, one left shoulder repair, one left biceps reattachment, one right shoulder repair in May and a right knee meniscus cleanup that's still fresh. These aren't war wounds. They're receipts from refusing to redesign my athletic identity when my body started sending increasingly urgent memos.

What Redesigning Actually Means

Here's what I don't mean: lowering your standards to "I'm just happy I can still play." That's surrender dressed up as acceptance. What I mean is asking yourself a creative, additive question: Given the body I have, what's possible now that wasn't possible before?

I know the reflexive answer. "Less! Less is what's possible, Paul. Thanks for asking."

But that answer comes from a deeply ingrained belief many of us inherited from our 20s and 30s— that athletic ability means speed, power, strength and recovery. We're still measuring ourselves against our 35-year-old selves, even if we've buried that habit deep in our subconscious.

What if your 60-year-old body, with all its limitations and accumulated damage, also came with capabilities your younger self didn't have?

The Athletic Skills You've Actually Gained

Your 60-year-old brain possesses pattern recognition your 35-year-old brain couldn't touch. You've played thousands more games, won or lost thousands more points, learned a thousand more lessons about improvising and adapting. You've banked years of athletic experience. You know how to win smart.

Your trained 50- or 60-year-old body also has movement efficiency your 35-year-old body didn't need as much. Leverage, timing and positioning become core elements of what's called neuromuscular training — refining movement patterns and increasing body control in ways proven to improve athletic technique.

This matters because your 60- or 70-year-old nervous system can be more precise than your younger one. You may be slower, but you can be more accurate. You can still hit a target. Maybe you can hit that target more often now than in your relative youth.

Neuromuscular training — also called agility body control training — develops muscle memory that optimizes athletic movement. Single-leg exercises like lateral lunges or star squats qualify. So do landmine exercises, where you lift the weighted end of a barbell. Even learning a beginner martial arts routine counts.

The Discipline Problem

I know firsthand how difficult it is to stop training the way you've grown accustomed to training. Adjusting your expectations to what your body can reasonably handle in weight, stress and repetition feels like betraying your athletic identity. Otherwise, you're basically queuing up for surgical intervention.

Which brings me back to those seven surgeries.

The hidden cost of being broken

Simply continuing to play hard with the same athletic tenacity you've always exhibited isn't a winning strategy. Not just because surgery involves long recovery periods and potential complications. The real cost — the one I didn't anticipate — is the enormous non-athletic price you pay for being unable to move your body, raise your heart rate or break a sweat for weeks or months at a time.

These costs often show up as elevated stress from your suddenly sedentary post-operative recovery. This stress may be invisible to you, but glaring and obvious to those who love you.

Designing Your Future Athletic Self

Here's the challenge: Stop trying to be the athlete you were. Start designing the athlete you are becoming.

Ask yourself these questions. What's my current athletic identity costing me? Or those around me? What would I do differently if I weren't trying to prove I'm still young or competing with that 28-year-old solely in my own mind? What's possible now that I've been too resistant or proud to try?

Then — and this is the important part — actually redesign. Change your training. Lower your daily pain threshold. Slash the cost of whatever you're currently calling victory.

The only obstacle between you and twenty more years of athletic life is your willingness to let go of the force of nature you were 15, 20 or 25 years ago and get curious about the 60-, 65- or 70-year-old athlete you're going to become.

That athlete exists. You just have to stop trying so hard to be someone else.

To find out more about Paul Von Zielbauer and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

Photo credit: Alonso Reyes at Unsplash

View Comments