By Carl H. Larsen

It's hard to find a good piece of bogtrotter cake. Unless, that is, you're in the Cafe Twit at the Roald Dahl Museum in Great Missenden, England, about an hour northwest of London.

Oh, and what a cake it is — similar to chocolate fudge with layers of spongy cake and a creamy chocolate icing.

You may remember Bruce Bogtrotter, for whom this divine confection is named, as the young boy at Crunchem Hall school who stole a piece of cake from the school's fearsome headmistress, Miss Trunchbull, in Dahl's classic 1988 book "Matilda."

As the mischievious and subversive author writes: "He thinks he's got away with it, but the Trunchbull is not one to take such insolence lightly. She devises a very particular punishment for this slightly greedy young boy —- and the whole school are invited to watch."

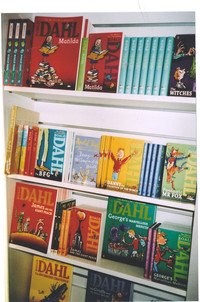

Seemingly these days, there's no getting away from Roald Dahl characters such as the Trunchbull, the Oompa-Loompas and the great chocolate-maker himself, Willy Wonka. Besides "Matilda," a favorite musical playing in London's West End and on Broadway, and the musical "Charlie and the Chocolate Factory," now playing in London and bound for Broadway, Dahl's works can be seen on film as well as onstage.

Hollywood earlier this year released a Steven Spielberg movie adaptation of Dahl's personal favorite, "The BFG," and fans of the late Gene Wilder will always remember his starring role as Willy Wonka in the 1971 film, an adaptation of Dahl's "Chocolate Factory" that returned in 2005 with Johnny Depp in the lead role.

There's a reason for this renewed interest in an author credited with selling 250 million books. September 2016 marks the 100th anniversary of Dahl's birth. The English-born writer, who died in 1990, today ranks alongside Harry Potter British creator J.K. Rowling, America's Dr. Seuss (Theodor Geisel), Sweden's Astrid Lindgren and Canada's Lucy Maud Montgomery as among the greatest authors of children's literature from the 20th century.

Directed by his literary estate, events coinciding with the anniversary are being held around the globe. The New York Times wrote: "The goal ... is wildly ambitious: to have every child in the world engage with a Roald Dahl story." The newspaper reported there are 23 television, film and stage projects in development, "as well as a Dahl-themed invention kitchen and book-inspired apps."

That is all well and good. But most vividly, Dahl springs back to life at the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre in Great Missenden, a quiet English village where the author lived and worked for 36 years.

Taken from his nearby home, Dahl's backyard writing hut is a prime attraction, with nary an item missing since he last wrote there. There's the big easy chair he sat in while composing stories, shunning a desk because of an old war injury. Most surprising is the fact that Dahl didn't type. He wrote on American legal pads, using pencils. Among the mementos in the hut is a ball made of chocolate candy wrappers he shaped as a young boy— and a hip bone, removed from him during surgery.

You can step into Miss Honey's classroom from "Matilda," explore the cockpit of a Gladiator to learn about Dahl's role as a pilot in the Royal Air Force and examine that particular lexicon created by Dahl known as gobblefunk, used by him in his stories. Among Dahl creations are lickswishy: a lickswishy taste or flavor is gloriously delicious; phizz-whizzing: if you like something or someone; wondercrump: wonderful or splendiferous; snozzberry: a type of berry you can eat"; scrumdiddlyumptious: food that is utterly delicious; flushbunking: makes no sense whatsoever.

A great outing for children, particularly those between 6 and 12, the museum also holds up well for adults in presenting the many-faceted and complex life of Dahl, an author who dwelled on the dark side.

Visitors learn about Dahl's work as a writer of macabre short stories for adults, some appearing in The New Yorker and Playboy. One of his best-known stories is "Lamb to the Slaughter," which was adapted for TV. In it, an unfaithful husband is beaten to death by his wife with a frozen leg of lamb. When police arrive to investigate, she offers them the lamb for dinner, eliminating the murder weapon.

Dahl's heroic service early in World War II as a pilot and ace for the RAF also makes a good story. Suffering from injuries in a crash, he was dispatched to Washington, D.C., as a military aide in the British embassy. A dashing young officer in uniform, he soon became quite a ladies' man among the city's upper crust, attending endless cocktail parties and dinners with executives and politicians. But in reality he was a spy for the British government, reporting home to Churchill on President Franklin Roosevelt and on American intentions and capabilities.

Not much of a student, Dahl's days in boarding school also are explored. He was born in Cardiff, Wales, of Welsh-Norwegian parents. Boarding school gave him much of the material for his later stories.

The Dahl story also is picked up in Cardiff. It focuses on the Norwegian Church Arts Centre on Cardiff Bay, where his family and the city's Norwegian community worshipped —- and where he was baptized — and on his neighborhood candy shop, which became a Chinese carryout restaurant.

A blue plaque marks the storefront where Dahl, as a boy, would stop by to buy sherbet suckers and licorice bootlaces.

In his autobiography, "Boy," he described the store owner as "a small skinny old hag with a moustache on her upper lip, little piggy eyes and mouth as sour as a green gooseberry."

It was here that Dahl once put a dead mouse into a candy jar, getting him into a world of trouble with his school headmaster. Still, the candy shop outside Cardiff is remembered as being the inspiration for some of his stories.

The museum in Great Missenden also has put together a series of walks through the town and surrounding countryside, going past places with strong connections to Dahl, who is buried in a nearby churchyard. His first wife was the American actress Patricia Neal. At the village post office, letters to Dahl from fans still arrive. At one time he was receiving 4,000 letters a week.

In response, in 1986 he wrote a poem to schoolchildren, sent to classes around the world:

"Dear children, far across the sea,

How good of you to write me.

I love to read the things you say

When you are miles and miles away.

Young people, and I think I'm right,

Are nicer when they're out of sight."

With his quick wit, his sometimes dark and brooding personality and never-boring exploits, Dahl's life is a treat to explore for those of any age. It's "um-possible," as Dahl himself would say, not to be impressed.

WHEN YOU GO

Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre, 81 High St., Great Missenden, England, is a 40-minute train ride from London's Marylebone Station and then a short walk: www.roalddahl.com/museum.

Visit England: www.visitengland.com

Visit Wales: www.visitwales.com

VisitBritain: www.visitbritain.com

Carl H. Larsen is a freelance travel writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

View Comments