By Sharon Whitley Larsen

As I stood by a charming stone cottage in this peaceful village, the heart of England's Peak District, and watched a homeowner sweep her walkway on this crisp, sunny day, I was stunned to read the plaque in front. Once — nearly 350 years ago — the happy Siddall family had lived here. Then one by one they were struck down by the plague.

First there was Richard, age 11, who died on Sept. 11, 1665. He was followed within weeks by his sister, Sarah, age 13, then his father and three more sisters. Another sister died in April, and by Oct. 17, 1666, when his mother died, the family was gone — except for young Joseph, age 3, who survived.

It's hard to imagine the horror of an illness that wipes out not only most of one's family but neighbors, friends — nearly an entire town. Of the 350 villagers in Eyam (pronounced "eem"), 259 died this horrible death, including 58 children. Now, with the recent spread of the frightening Ebola virus, we're vividly reminded of the terrifying 17th century bubonic plague.

Caused by a bacterial infection, the plague hit its victims with swollen lymph nodes, fever, chills, headache, fatigue and muscle aches. Symptoms could include a rosy-red rash and black boils from dried blood under the skin caused by internal bleeding that appeared in the armpits, neck and groin. The "Black Death," as it was known, could be excruciatingly painful and horrible for others to watch.

What makes this bucolic, mountainous Derbyshire village (known as "The Plague Town") so unusual is not only that the plague wiped out such a high number of residents in such a short time but also the way its devastated townsfolk reacted to the deadly infectious disease. They sacrificed themselves so others could live: Courageously cordoning themselves off from the outside world, the Eyam villagers kept the evil event from spreading further, and this was the last place it hit in England.

The plague, which first surfaced around the late 1320s in China, spread rapidly by fleas and rats via trading ships. Eventually it hit Europe and during the mid-1300s killed some 25 million, one-third of the population. Later, between December 1664 and the beginning of 1666, some 100,000 died in London, about one-fifth of the population. It was during this time, the summer of 1665, that a resident of London — 150 miles away — shipped an Eyam tailor some cloth. The package of old clothes and cloth patterns arrived wet, and the tailor's assistant, George Viccars, who lived with the family, was told to take the cloth outside and spread it out to dry.

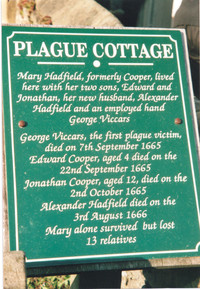

Obviously no one realized that the damp cloth was already infected by fleas that carried the curse of the plague. In just four days Viccars was dead, the first victim in Eyam to died of the plague, and he was buried on Sept. 7, 1665. A plaque in front of the home, "Plague Cottage," lists some of the household members who died within a few days of each other. Only one, the tailor's wife, Mary, survived. She lost 13 relatives.

Another plaque summarizes the horror of the Hawksworth family, who lived nearby. The husband, Peter, was the third victim of the plague in the village; his son Humphrey, 15 months, died just weeks later. And Peter's wife, Jane, was the sole survivor of the household, eventually losing 25 relatives.

During the next horrifying 13 months, the stunned Eyam townsfolk quickly buried their dead, trying in vain to keep the devastating disease from spreading. In fact, during these mournful months of the plague, funerals were not held; families buried their own in the front or back yards, sometimes using old doors or chairs as biers.

Once the last family member had died off, it became the horrendous official job of Marshall Howe, a courageous villager, to do the burial. He would tie a cord around the neck or foot of the corpse so as not to touch it and drag it to a nearby garden or field where he had dug a grave. For nearly three months he performed this awful task, never dreaming that he would end up fatally infecting and burying both his wife, Joan, and only son, William, within days of each other in August 1666. Deeply grieving, he blamed himself for bringing the disease home to them. Miraculously, he survived the epidemic and lived another 32 years.

For a couple of generations, Eyam parents would admonish their children to obey or else they would send for Marshall Howe. And some today believe that the popular children's nursery rhyme, "Ring around the rosy, pocket full of posy. Ashes, ashes! We all fall down!" symbolizes the plague.

Once summer arrived, the church's wise rector, the Rev. William Mompesson, closed the Eyam Parish Church to worshippers, fearing that the hot weather would make things worse. Instead they met in an outdoor enclave where they prayed twice weekly and held a Sunday service. Today it's the site of the annual Plague Commemoration Service, which is held the last Sunday in August. The Eyam Museum, which is highly ranked on TripAdvisor but was closed the day of my visit, pays tribute to the plague victims with many displayed items.

The pastor and his assistant, the Rev. Thomas Stanley, had earlier admonished the townsfolk not to cross a certain boundary surrounding the village, designated by large stone and mound landmarks. It was the "Boundary Stone" and "Mompesson's Well" where outsiders (earlier notified by the pastor) would quickly leave food and medical supplies, many donated by the Earl of Devonshire from his nearby Chatsworth House. Then they would flee, lest they themselves fall ill. Village volunteers would retrieve the valuable items, leaving coins for payment that were then washed and disinfected with vinegar.

It was because of this self-enforced isolation that the plague did not spread to surrounding areas. The Rev. Mompesson visited 76 parish families during the ordeal, comforting and praying with them. He and his wife, Catherine, had sadly and reluctantly sent their two young children, George and Elizabeth, ages 3 and 4, to live with relatives in Yorkshire, and they survived. However, Catherine, who had stayed behind to be at her husband's side, died of the plague at age 27 on Aug. 25, 1666, further devastating the townsfolk. She is buried in the churchyard.

Just outside town are the "Riley Stones" — a small graveyard where the farming Hancock family is buried. Mrs. Hancock, who survived the plague, had the incomprehensible, tortuous task of burying her husband and six children in eight days. She had one surviving son, who had left the area prior to the plague breakout.

By early November that year the deaths ceased. As a precaution, clothing and furniture were burned, and the bare necessities that remained were fumigated. As the Rev. Mompesson (who moved from the village three years later) wrote to a friend on Nov. 20, 1666: "Our town has become a Golgotha, the place of a skull; and had there not been a small remnant left, we had been as Sodom, and like to Gomorrah. My ears never heard such doleful lamentations — my nose never smelled such horrid smells, and my eyes never beheld such ghastly spectacles."

WHEN YOU GO

www.eyamvillage.org.uk

www.derbyshireuk.net/eyam.html

www.eyam-museum.org.uk

www.nationaltrust.org.uk/eyam-hall-and-craft-centre

www.visitpeakdistrict.com/bakewell-eyam/details/?dms=3&venue=6070450

www.visitengland.com

www.britrail.com

Sharon Whitley Larsen is a freelance writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com

View Comments