By Glenda Winders

President John F. Kennedy once famously told a group of Nobel Prize winners he was honoring that the White House had never had so much brainpower under its roof except when Thomas Jefferson dined alone. Inspired by his comment and intrigued by all the conflicting accounts I'd read about Jefferson, I set off with a companion in pursuit of this enigmatic statesman. And find him we did, but not always where or in the ways we had anticipated.

Our destination was Charlottesville, Virginia, where we figured the logical first stop would be Jefferson's home at Monticello. Since visitors' tickets are dated and timed, we had a day to kill before we could enter, so we spent part of it touring Ash-Lawn-Highland, the nearby home of President James Monroe. When the docent there mentioned in passing that Jefferson had a second home where he went to get away from the crowds that visited Monticello, a woman in our tour group turned to me and whispered, "We liked it better." That's all it took.

Two days later we made the 90-minute drive to Lynchburg and Jefferson's second home, Poplar Forest. We liked it better, too, and so did Jefferson, it turns out. He came here, he said, to experience "the solitude of a hermit." He wrote that it was the best of all his treasures and perhaps a better design than Monticello because it was "more proportioned to the faculties of a private citizen." Indeed, we heard other visitors murmuring to one another that they could easily live here.

Jefferson inherited the 4,800-acre property from his father-in-law and built the home between 1806 and 1816. He disliked Colonial architecture, so like the Monticello design, this one incorporated Roman and Greek aesthetic principles and was on one level in the manner of homes he had observed when he was an ambassador in Paris. His architectural role model was Andrea Palladio (1508-1580), who made a practice of integrating the structure with the landscape.

On first sight the columned brick house resembles Monticello, but this one is an octagon made up of a cube in the middle surrounded by four elongated octagons. The octagon theme extends right out to the "necessaries" — outhouses built in the same shape.

Our docent, Rob Palmer, pointed out that Jefferson, a lifelong farmer, didn't just retreat here to think and write. Like his other home, this was a fully self-sustaining plantation. He came here in all the seasons and especially in spring for planting. With the help of several slaves he raised tobacco at first and then replaced it with wheat, which was more beneficial to its users, took less work and didn't destroy the soil.

Palmer said it took Jefferson two days to ride here on horseback from Charlottesville, and he usually stopped midway to spend the night at an inn. During one such stopover he stayed up late having a discussion with another guest who was a minister. The next morning the guest told the innkeeper he thought the man he had been talking to must be a minister, too, because of his extraordinary knowledge about philosophy. Imagine the man's surprise when he found out he had spent his evening with the president.

After Jefferson's death the house was sold and eventually fell into disrepair until 1983, when it was rescued by a group of citizens. Today it is undergoing extensive restoration using Jefferson's notes and archeologists' findings to bring it back to what it would have been like when he lived there. Restorers are using custom-made reproduction bricks and authentically re-created mortar, and they are cleverly leaving one wing unadorned so that visitors can see how substantially the building was constructed. When a tree fell that would have been there during Jefferson's time, builders incorporated its lumber into the project.

The previous day we'd taken our tour of Monticello, starting at the visitors center and riding a bus to the top of the "little mountain" — monticello in Italian. The interior was fascinating and the gardens beautiful, but our favorite vista was the side of the house that our guide called "the nickel view" — the dome, columns and symmetrical wings we had seen on coins since childhood.

Jefferson called his primary home "My essay in architecture," while some of his neighbors considered it a cluttered curiosity. Then, as today, it was filled with his unusual range of possessions —- from American Indian artifacts collected by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and a Chinese gong for striking the hour to his maps, 7,000-book library and indexed correspondence of 19,000 letters. We also got to see his "polygraph" — a contraption that linked two pens together so Jefferson could make copies of everything he wrote.

Since people came from far away to see the home and hope for a glimpse of its owner, Jefferson's policy was to feed them and put them up for the night. When the crowds got too much for him, he decamped to Poplar Forest.

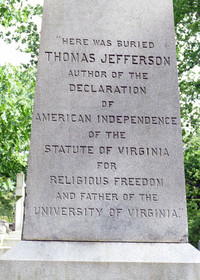

When our tour was over, we opted to take the bus just partway down and get off at Jefferson's gravesite. Author of the Declaration of Independence, he died here on July 4, 1826 — the document's 50th anniversary. From there we walked the rest of the way back to the visitors center on a path through the forest that Jefferson himself must have taken.

Our Jefferson-connected discoveries continued beyond our visits to his homes, too. During a downtown tour with Steven Meeks, president of the Albermarle Charlottesville Historical Society, we learned about Jack Jouett, the "Paul Revere of the South" who rode through the night to warn Jefferson (then governor) that British troops were headed to Monticello, where he and Virginia legislators had fled.

"Unfortunately no one wrote a famous poem about him," Meeks said. "But if it hadn't been for him, history might have turned out very differently."

At Albermarle Ciderworks Jennifer Detweiler told us stories while she poured our samples of their product.

Jefferson loved all things European and especially French, she said, but French wines were expensive to import and the grapes difficult to grow. That being the case, his everyday libation was hard cider. We couldn't resist bringing home a bottle of Jupiter's Legacy — partly because it tastes more like champagne than apple cider but mostly because it honors Jupiter Evans, the slave who oversaw its production at Monticello.

At age 82 and in "retirement" Jefferson founded the University of Virginia, designing its buildings and curriculum and watching its construction from Monticello by means of a telescope trained on the campus through a clearing in the forest created for that reason.

When we took a walk through the campus to see the Rotunda and The Lawn at its heart, we very much felt Jefferson's presence. In the drama department that was gearing up for this summer's Heritage Theater Festival we chatted with Robert Chapel, the festival's producing artistic director, who told us our experience was not unusual.

"Jefferson's tombstone doesn't mention he was president," Chapel said, "but it does mention that he started this university."

With our days in Charlottesville over we headed on to Colonial Williamsburg, where we took a tour of the Governor's Palace. When the costumed docent explained that this is where Jefferson had lived when he was governor we gave each other a look. We both had the feeling that Jefferson had ridden right along in the car with us.

WHEN YOU GO

We stayed at the Oakhurst Inn — a real find. It is tucked into a quiet cul-de-sac close to the University of Virginia, but it also has easy access to main thoroughfares through the city. Guests enjoy healthy breakfasts served in a cottage on the grounds: www.oakhurstinn.com.

For general information: www.visitcharlottesville.org

Monticello: www.monticello.org

Poplar Forest: www.poplarforest.org

Williamsburg: www.colonialwilliamsburg.com

Albemarle Ciderworks: www.albemarleciderworks.com

Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society: www.albemarlehistory.org

Heritage Theatre Festival: www.heritagetheatrefestival.org

Glenda Winders is a freelance writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

View Comments