Week of September 24-30, 2017

It was a cool, crisp autumn day in Pennsylvania in 1966, and I remember it well. There I sat in Mrs. Moyer's 10th grade geometry class daydreaming out the window, as I often did, and pondering everything except acute angles, midpoints and spheres.

"After all," I reasoned, "what use is knowing that a circle can be broken into 360 equal parts, each part one degree wide? I've got better things to think about!"

I'm embarrassed to say that this scene played itself out daily while I was in school. The irony is that out that very window existed circles that I would use just about every day of my professional life.

We can't see them, of course, but the heavens contain two so-called great circles that help us define the position of any celestial object.

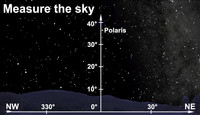

The easiest to imagine is the one we know as the horizon. Starting at due north, scan your gaze eastward along the horizon and divide it into 360 equal pieces. One degree is approximately the width of your little finger held at arm's length. The width of your fist — from thumb to little finger — held at arm's length spans about 10 degrees.

We always measure azimuth eastward along the horizon from true north. For example, something that lies due east is said to have an azimuth of 90 degrees east of north. And something in the north-northwest might have an azimuth of 315 degrees east of north.

Try this next time you're under the nighttime sky and you'll find you've got an instant ruler on which to measure a celestial object's azimuth. It provides a more precise way of describing directions than such broad terms as "south" or "northeast."

There's another great circle that we can imagine. It begins at any point on the horizon, passes directly overhead (the zenith) and continues down to the opposite side of the horizon. Since it's technically only half a circle, we can divide it into 180 degrees and use it to measure the altitude of any celestial object. You can use your fist for this as well.

Check it out with Polaris, the North Star, which remains relatively fixed in our sky. If you live in San Diego, for example, you'll find that the altitude of Polaris is about 32 degrees. From the New York City area, Polaris appears about 41 degrees above the horizon. That's because the altitude of the North Star conveniently equals your latitude.

There are other "great circles" in the heavens as well: the ecliptic, the meridian, the celestial equator ... and knowing these help astronomers grasp the layout and movement of our starry night sky.

It was back in the autumn of '66 that something clicked inside of me. Perhaps it was a clonk on the head during football practice, but more likely it was the skill of my geometry teacher who never gave up on that goofy kid in the third row.

Soon after I became fascinated by how one can measure the world and the universe with geometrical figures and angles, and how important this is to astronomers.

And for that gift, Mrs. Moyer, I thank you ... beyond all measure!

Visit Dennis Mammana at www.dennismammana.com. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

View Comments