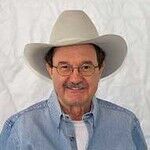

Wanting to be like his great-grandfather, grandfather and father, Carlton Pearson set his young heart on becoming a Pentecostal preacher.

By 5 years old, the African-American boy was preaching to other kids in his poor Southern California neighborhood. A natural, he grew into an unusually gifted preacher and gospel singer at storefront churches, the kind with colored plastic lining their windows because they can't afford stained glass.

Pearson's talent widened his world: He went on to study at Oral Roberts University, serve on the evangelical school's board of regents, move in the most elite white evangelical circles, chat with Republican presidents and host his own three-hour gospel TV show.

He preached that AIDS was God's punishment for homosexuality, and spoke in tongues and laid hands on homosexuals to — as he saw it — cast out their demons.

But a few years ago, Pearson lost the trappings of success — including his mega-church, where collection plates overflowed with $60,000 a week. He found a more emotionally rewarding way of relating to God and people.

How?

He stopped believing in hell. He was no longer willing to preach that a loving God would doom most of humanity to a "customized torture chamber." Deciding that "if Jesus is the savior of the world, then the world is saved," Pearson started spreading "a gospel of inclusion" — proclaiming that everyone is saved, not just Christians.

Branded a heretic, shunned by other mega-church evangelists, Pearson initially felt shattered. But Jews reached out to him and so did gay students at Oral Roberts University, who asked if his inclusive gospel included them. Yes, he replied. Soon, he was invited to preach at a gay San Francisco church. Afterward, everyone hugged him.

"I hadn't been loved like that in months by anybody, especially Christians," Pearson recalls.

And then the lesbian pastor washed his feet. "Oh my God, it was one of the holiest moments in my whole Christian life. That female gay woman with all these gay people weeping and singing and loving this (so-called) heretic and washing his feet. The people I had once denied and denounced were now my only friends," he recalls.

Pearson committed himself to being a loving brother to those of us who're gay. This spring, he led several hundred religious leaders in lobbying Congress to protect gay and transgender people from hate crimes and job discrimination.

"I am not telling people they have to love gays. I am telling people they get to love gays. ... All people want is permission," Pearson says.

He's helping the National Black Justice Coalition (NBJC) launch its "Faithful Call to Justice." Black and racially mixed churches are being asked to have gay-friendly sermons or messages in their bulletins on the first weekend in June. (If you'd like to participate, email srhue at nbjc.org.)

"The black church is where a lot of black people take their cues about lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people," notes NBJC spokesman Herndon Davis.

Pearson says: "We have always had gays in the church, and some of the best music in the African-American church was written by gays. We've sung their songs and cursed their souls."

Pearson's faith in a God too loving to shun anyone opened new doors in his heart. And now he's working to help the black church and the rest of the nation walk through them.

Deb Price of The Detroit News writes the first nationally syndicated column on gay issues. To find out more about Deb Price and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate web page at www.creators.com.

View Comments