Chief Justice John Roberts' opinion this week to uphold the Affordable Care Act was good news for the White House and good news for the Supreme Court, as well.

A few weeks ago, a New York Times/CBS poll showed that only 44 percent of Americans approve of the job the Supreme Court is doing — a slide from 66 percent approval in the 1980s. Three-quarters say the justices' personal or political views sometimes affect their decisions. Only 1 in 8 say legal analysis alone guides the justices. Sixty percent agree with the statement that "appointing justices for life is a bad thing because it gives them too much power."

A 5-4 vote to overturn the health care law — the result expected by many court experts — would have fed the perceptions that led to the declining approval of the court.

In contrast, Roberts' decision to join four colleagues from the left to find the law constitutional was an act of exquisite statesmanship — enhancing the court's reputation, deferring to the country's elected leaders, sparing the nation more political acrimony and delivering a jolt to the gathering view that the Roberts court is driven only to seek conservative results.

At the same time, the Roberts opinion is not nearly so moderate as conservatives fear or liberals hope.

Roberts found the act constitutional under the taxing authority and declared that the individual mandate is not constitutional under the commerce clause, writing, "The Framers gave Congress the power to regulate commerce, not to compel it."

Roberts wrote: "The individual mandate ... does not regulate existing commercial activity. It instead compels individuals to become active in commerce by purchasing a product, on the ground that their failure to do so affects interstate commerce. Construing the Commerce Clause to permit Congress to regulate individuals precisely because they are doing nothing would open a new and potentially vast domain to congressional authority."

Jeff Shesol, author of "Supreme Power" and a friend of mine, wrote in Slate: "Justice (Ruth Bader) Ginsburg and the court's liberals, in their concurring opinion, make clear what is really happening here: The establishment of 'a newly minted constitutional doctrine' — a sort of de facto, save-it-for-later majority opinion, effectively endorsed by the four dissenters."

This new doctrine puts new limits on the power of Congress.

Conservative columnist George Will cheered the move: "By persuading the court to reject a Commerce Clause rationale for a president's signature act, the conservative legal insurgency against Obamacare has won a huge victory for the long haul."

Roberts' interpretation of the commerce clause is not just conservative; it is very conservative. Republican-appointed appellate judges Jeffrey Sutton and Laurence Silberman both upheld the individual mandate under the commerce clause.

Silberman wrote in his November 2011 opinion, "No Supreme Court case has ever held or implied that Congress's Commerce Clause authority is limited to individuals who are presently engaging in an activity involving, or substantially affecting, interstate commerce."

Silberman also wrote: "To 'regulate' can mean to require action, and nothing in the definition appears to limit that power only to those already active in relation to an interstate market. Nor was the term 'commerce' limited to only existing commerce."

In response to the notion — later expressed in the Roberts opinion — that upholding the ACA under the commerce clause would "open a new and potentially vast domain to congressional authority," Silberman wrote, "The health insurance market is a rather unique one, both because virtually everyone will enter or affect it, and because the uninsured inflict a disproportionate harm on the rest of the market as a result of their later consumption of health care services."

Finally, Silberman wrote in the closing paragraph of his 37-page opinion, "The right to be free from federal regulation is not absolute, and yields to the imperative that Congress be free to forge national solutions to national problems."

Silberman is not some casual figure in conservative jurisprudence. He is a renowned conservative jurist appointed by President Ronald Reagan. Now a senior judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2008 by President George W. Bush and was described in the White House press release as "a stalwart guardian of the Constitution."

That Roberts' view of the commerce clause is sharply to the right of Silberman's is notable.

Roberts let stand an act he had the votes to overturn. Given the furious debate it would have triggered, the country owes him a debt of gratitude. At the same time, his formulation of a new commerce clause doctrine that is not a consensus view even among conservatives does not appear to be an act of restraint.

The doctrine's ultimate impact will depend on how many justices subscribe to it. With four justices now in their 70s, that may depend on who wins in November.

As if we needed anything else to raise the stakes for this election.

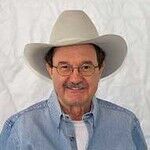

Tom Rosshirt was a national security speechwriter for President Bill Clinton and a foreign affairs spokesman for Vice President Al Gore. Email him at [email protected]. To find out more about Tom Rosshirt and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

View Comments