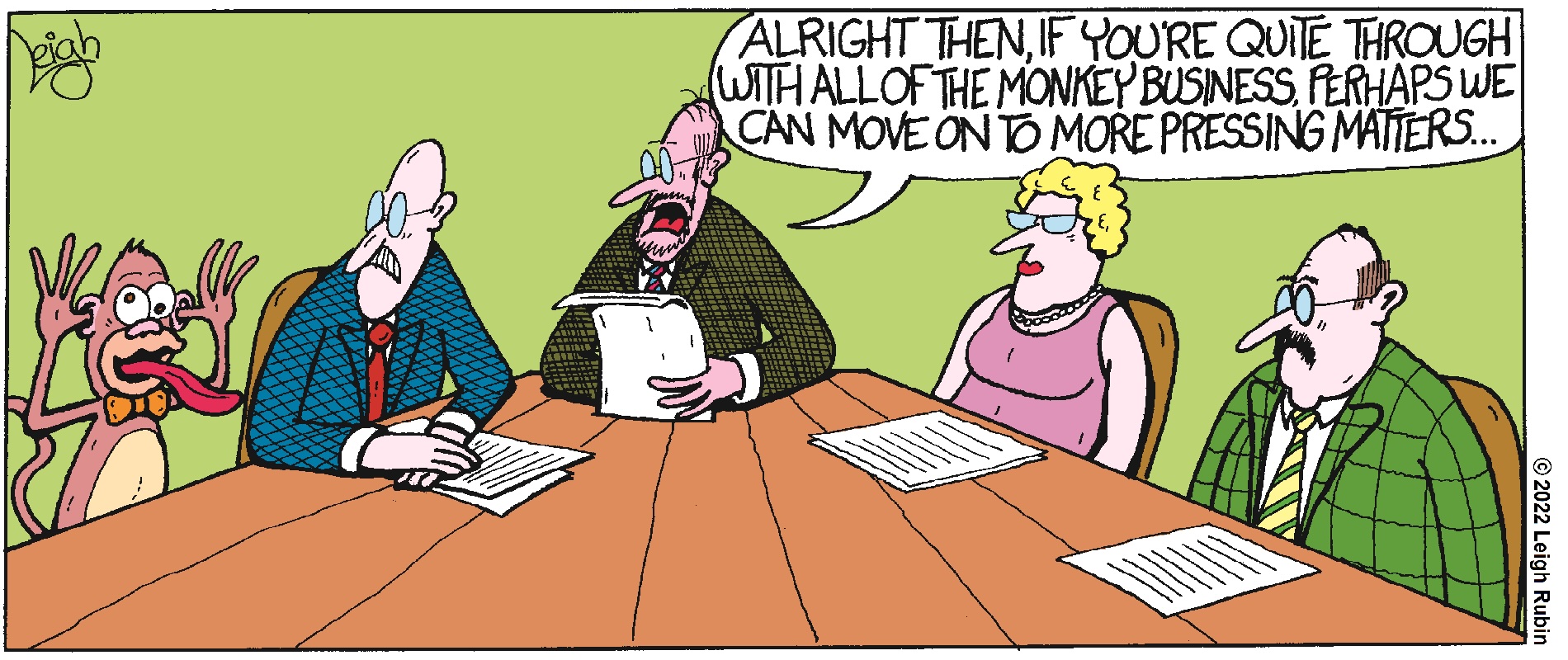

Syndicated cartoonist Leigh Rubin explores the creative process in his new book, Think Like a Cartoonist: A Celebration of Humor and Creativity, published by RIT Press. Rick Newcombe wrote this essay for the book.

Imagine being thirty-four years old and running the third-largest newspaper syndication company in the world and working with cartoonists who had created some of the most successful comic strips in history, such as Dennis the Menace, Wizard of Id, B.C., Steve Canyon, Mary Worth, and Momma.

That was me—traveling the world by flying first class, staying at five-star luxury hotels, and dining at some of the finest restaurants on the planet as well as having a huge staff and enormous company resources at my disposal whenever I needed something.

Then, out of the blue, the company was sold, and I was suddenly out of a job.

I was thirty-six at the time, married and with two children, a mortgage, and a whopping $900 in my bank account, which was my total net worth. I didn’t even own a car. I had been driving a company car, and on the day I left the office for the last time, I drove home and went for a run to clear my head. When I returned, my wife was fighting back tears. She said that two big guys had just come to the house to take back the company car. She was standing there with our two children, ages seven and four, watching them drive off with what had been our primary means of transportation.

How do you connect the dots when you can’t even see straight?

Well, I calmed down and thought about what I had learned in fourteen years in the business world. I had become an expert in comic strips and cartoons, and I knew that I could always make a living syndicating them. But I also knew that I did not want to be so vulnerable again, which meant that I wanted to start my own syndicate, and I knew it would have to be different.

That’s when I thought about the one issue the majority of cartoonists were complaining about: Who should own the cartoon, the syndicate or the cartoonist? At the time, the answer was the syndicate.

When I first met the legendary Milton Caniff, we had lunch in New York, and he told me about his career. During the 1940s he had created the most popular comic strip in the country at the time, Terry and the Pirates, featuring the famous Dragon Lady character. He said that since he had created this comic strip, he thought it was only fair that he own it, but his syndicate said, in effect, “Tough luck. We own it.” He felt so strongly about the issue that he walked away and created a whole new comic called Steve Canyon, but only on the condition that he be allowed to own it, which he was.

Hank Ketcham told me that he had been “hog-tied” by his syndicate ever since he created Dennis the Menace. He had filed a lawsuit against his syndicate in the 1960s, and he lost.

Johnny Hart, creator of B.C. and Wizard of Id, said that he had secured ownership of his two strips, and he encouraged me to start the first syndicate granting ownership to cartoonists. Same with Mell Lazarus, creator of Momma and Miss Peach. They said that if I started such a syndicate, they would eagerly join as soon as their contracts allowed.

So I started researching this issue and discovered that it went back to the beginning of cartoons in newspapers.

I learned that the very first comic strips increased newspaper readership dramatically. The Yellow Kid was a character in Richard Outcault’s comic strip, Hogan’s Alley, which ran from 1895 to 1898 in the New York World, which was owned by Joseph Pulitzer. But William Randolph Hearst owned the New York Journal, and he was determined to win the circulation war with Pulitzer, so he hired Outcault and ran the Yellow Kid on the front page. Hence, we got the term “yellow journalism.” (Also, I suspect that the presses in those days occasionally bled yellow all over the page.)

In fact, cartoons were so good for business that Hearst decided it was not enough to run them or sell them to other newspapers; he needed to own them, and this became a mandate for the syndication company he founded in 1914, King Features Syndicate.

One of his most successful comic strips was The Katzenjammer Kids by Rudolph Dirks, which started in 1897 and was syndicated by King Features. At some point, Dirks asked Hearst for ownership of his creation, but Hearst said no. So Dirks filed a lawsuit—and lost.

Nothing had changed since then. As a budding entrepreneur, I knew that if Creators Syndicate were the first in history to grant ownership to the cartoonists—the name, the characters, and the likenesses—we would be creating a revolution among cartoonists, and that is what happened. True to their word, Johnny Hart and Mell Lazarus moved their strips to Creators as soon as they could. The legendary editorial cartoonist Herblock (Herb Block) of The Washington Post joined us as well.

But those early days were anything but luxurious. I started with a desk and a phone, flying coach, eating at my desk, working ’round the clock. But gradually, with grit, we prevailed. In 1988, we started syndicating one of the funniest panel cartoonists of all time—Leigh Rubin—creator of Rubes (and this book).

Creators Syndicate became a major success story and changed an entire industry—all because we connected the dots by listening to what was really bothering the cartoonists and giving them what they wanted.

Rick Newcombe is the founder and chairman of Creators Syndicate and has syndicated the Rubes cartoon since 1987. Newcombe is also the co-founder, with his son Jack, of Creators Publishing, which has published numerous bestselling books. In addition to Rubes, Creators has syndicated Wizard of Id, B.C., Archie, Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Batman, Zorro, Momma, Andy Capp, One Big Happy, The Other Coast, Agnes, Heathcliff, Herb and Jamaal, and dozens of other comic strips. The company also syndicates and publishes many of the best-selling writers and political cartoonists in the country. And yes, Rick Newcombe also is proud to count Leigh Rubin as a friend.